Salman Khoshroo: from Human to Post-Human in Painting and Sculpture

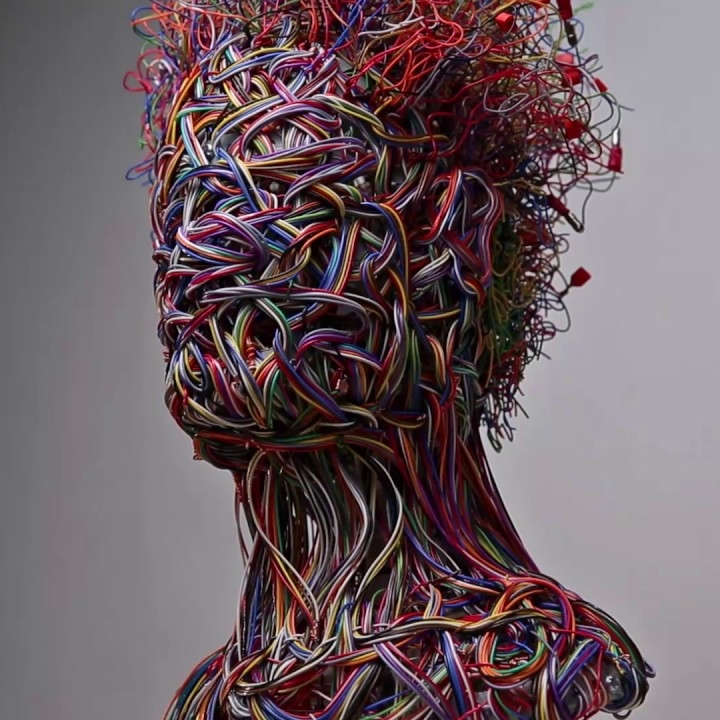

Salman Khoshroo’s diverse oeuvre encompasses many styles of painting, and, more recently, sculpture. ‘Head Jig’ (2017) and Entwire Series (2017-) use brightly coloured electrical wires wrapped around a wire frame to form the shape of a ‘human’ or ‘post-human’ head. In fact, Khoshroo’s evolution from painting the human to sculpting the post-human reflects the philosophical thought of the visionary futurist, FM-2030, as well as that of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. ‘Head Jig’ and Entwire Series’ ‘HEADMA01’ and ‘HEADFB01’ thus offer a clever commentary on aesthetic and philosophical concerns of the last forty years.

Salman Khoshroo’s paintings are the fruits of years of experimentation. In part, this is because his earliest and most impressionistic portraits often struggled to portray any positive emotions. Instead, they always managed to capture—wittingly or unwittingly—something of an existential angst in their predominance of whites, blues, pinks, browns, and blacks. Subsequently, Khoshroo began experimenting with a wider range of colours and styles and is now well-practised in Impressionism, Cubism, and Futurism. Consequently, he’s one of the most versatile portraitists working in the world today. Recently, he’s eschewed the facial detail of his earlier portraits in favour of bold sweeps of primary colour that nonetheless conform to the outline of a portrait. In Entwire Series, the brush and palette knife are then substituted for pliers as the brightly coloured insulating material of the wires replaces the bold primary colours of his paintings.

‘Head Jig’ and Entwire Series’ ‘HEADMA01’ and ‘HEADFB01’ might be described as robots. For e.g., ‘Head Jig’ adjusts its position as the cogs and gears that support it change theirs. It’s as if it’s following a conversation in the room. It suggests the ‘machine’ instead of the ‘human’. It’s as if the ‘organic’ capillaries and veins just under the surface of our skin are revealed as so many wires carrying electrical charge and data. It’s a ‘machine’ as much as it’s an artistic representation of the ‘human’. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus () famously opens with the section on ‘Desiring-Production’ wherein: ‘It is at work everywhere, functioning smoothly at times, at other times in fits and starts…it is machines—real ones, not figurative ones: machines driving other machines, machines being driven by other machines, with all the necessary couplings and connections. An organ-machine is plugged into an energy-source-machine: the one produces a flow that the other interrupts.’[1] Deleuze and Guattari thus brought the ‘machine’ and ‘flow’ of ‘desire’ into philosophical discourse proper. It’s tempting to think of the brightly coloured wires as carrying the competing and contradictory currents of our desire. It’s useful, then, to consider Khoshroo’s ‘Head Jig’ and Entwire Series in relation to ‘The Figurative Communication of Denis Sarazhin’.

In this article, it was argued that Sarazhin’s Pantomime Series (2016-) focusses our attention of the subject’s body by frustrating the viewer’s instinctive glance toward the subject’s face. Sarazhin’s ‘return to the body’ thus tacitly acknowledged post-structuralism’s critique of the singular person or subject. Instead, we’re all inhabited by competing and often contradictory thoughts and desires. Similarly, in Khoshroo, there’s no recognisable ‘subject’ as such. Instead, there’s only the outline of a face coloured in without reference to the sitter’s unique and individual features. ‘Head Jig’ and Entwire Series are amenable to interpretation along the lines of the post-human philosophy of the visionary futurist, FM-2030. So, who or what is FM-2030? FM-2030 was born or ‘launched’ in the year 1930 as Fereidoun M. Esfandiary before changing his name in 1970.

FM-2030’s philosophy revolved around a single question: ‘What is human?’ It’s the same question that artists often seek to answer in their portraits. FM-2030’s answer could easily describe the existential anguish that inhabits Khoshroo’s earliest portraits: ‘We are fragile, vulnerable, mortal, finite beings.’ We’re hopelessly evolved with the ‘survival emotions’ of ‘fear, love, territoriality, competiveness, aggressiveness, jealousy.’ Interestingly, FM-2030 referred the word ‘linkups’ to ‘marriage’ or other socially accredited human bonds.[2] Isn’t ‘linkups’ nothing but the ‘couplings and connections’ of one machine thus ‘plugged’ into another machine? FM-2030 argued that we’d reached an ‘evolutionary turning point’ where ‘we can no longer consider ourselves exclusively human’ because ‘the biological and terrestrial premises that have always defined the human, no longer fully apply.’[3] FM-2030 thus suggested that our current ‘names’ were the unnecessary relics of our past animal-human societies whereas, now, ‘the shift from animal-human to post-human is accelerating faster and faster and faster.’

‘[B]it by bit,’averred FM-2030, ‘we are de-animalising our bodies’[3] and moving into the post-human. Isn’t your phone as important a part of ‘you’ as your own body? Isn’t it just as essential for communication these days as your own voice? Isn’t your ‘facebook profile’ just as important as your real and living profile? FM-2030 argues that ‘so long as we are confined to this fragile, biological make up, there will always be inequality and human tragedy and human suffering.’ It’s impossible to recognise ‘survival emotions’ in Entwire Series because the small micro-expressions of the face are replaced with the wires. Instead, we’re offered the ‘human’ as ‘machine’ in an intimation of the post-human. It’s nicely thought-provoking work. Khoshroo’s a young artist who’s not scared to explore and master new areas. He’s definitely one to watch.

If you liked this article and would like to stay up to date with our future publications then click here to subscribe to our mailing list!

[1] Deleuze, G., & Holland, E. (2001). Deleuze and Guattari's Anti-Oedipus. London: Routledge.

[2] F.M. Esfandiary; Futurist Predicted Immortality. (2017). latimes. Retrieved 25 June 2017, from http://articles.latimes.com/2000/jul/11/local/me-50834

[3] Are You Transhuman. (1994). University of California.