Q&A: Dina Brodsky

Whilst most of us are currently lounging somewhere sunny, Dina Brodsky is working hard. This New York-based contemporary artist specialises in realist miniature paintings and cycles through Europe in the summertime to draw inspiration for her work. Scanning her environment as she travels, Dina sketches away the little gems she comes across, and later turn them into miniature, ultra-detailed oil paintings, on 2’’ diameter copper or Plexiglas discs.

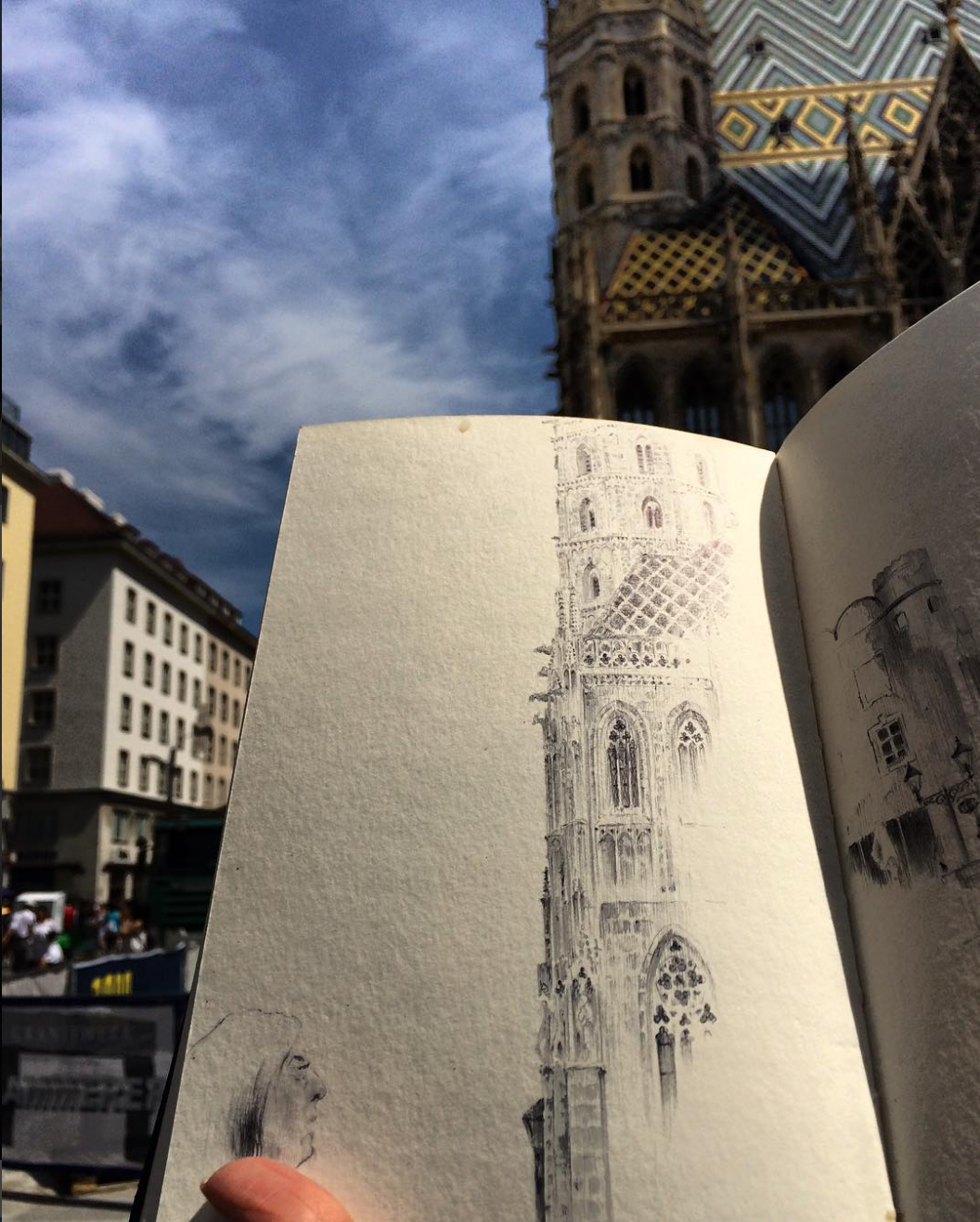

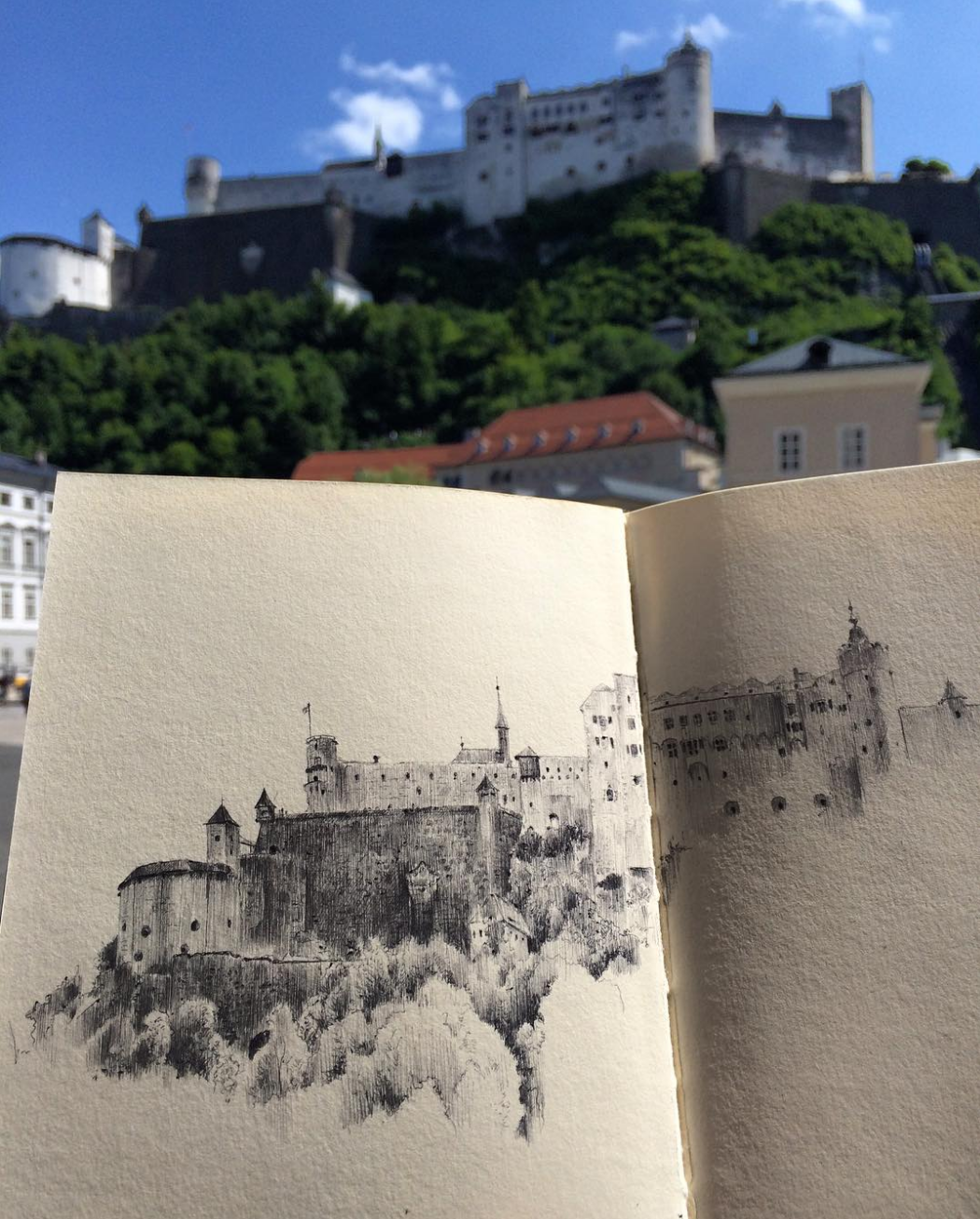

In Spring 2015, her solo exhibition Cycling guide to Lilliput at Island Weiss Gallery, New York, presented the result of her two passions: painting and long distance cycling. Between the Grand tour and the tour de France, Dina invites us on a fascinating journey through her personal outlook on trees and birds but also buildings, streets and people. Reduced to tiny, minute tondos, her work reminds us of Medieval manuscript illumination, combined with the precision and attention to detail of early Netherlandish or French realist painters. Jan van Eyck and Gustave Courbet would be proud of her wonderful, crooked trees and sun-kissed, earthy roads; The Venetian painter Canaletto would appreciate her fine black and white drawing of St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, uploaded on Instagram a few days ago.

BS: This summer you’ve been cycling in Central Europe, from Passau to Prague, via Vienna. How do you pick your destinations and plan your cycling route?

DB: When I was 19 I spent a summer hitchhiking and traveling by train all over Europe. That trip was full of adventures (of the kind that come with extremely bad planning), but also rushed — I felt like I got a very superficial glimpse of a lot of places that I would have liked to know more thoroughly. I was traveling with my first sketchbook, and drawing everywhere I went, but my drawings weren’t very good.

I always meant to come back to some of the places I briefly saw that summer, and have the time and the drawing skills to experience them properly. Vienna and Prague were two of the places I had really vivid memories of from that summer a long time ago, and this was my chance to draw them the way I wanted to. So I pick my routes based partially on memories, but also based on their cycling properties - I tend to follow rivers since the routes there tend to be flat and easy to cycle. Passau to Vienna was an organic choice since that route follows the Danube river and is an amazing bike trip.

BS: When we travel, many of us post pictures of ourselves near landmarks on social media. Instead, your Instagram is filled with photos of your sketchbook in front of their models d’après nature. Is this because you want to encourage us to look at the places we visit differently?

DB: It’s just an attempt to capture the way I felt, drawing and thinking in that place. I mostly photograph the pages that way to have a personal memory of the places I drew, along with the drawings — the cafes, park benches, or town squares the drawings were made in. But yes, I suppose I hope that it makes people slow down a bit when they see these landmarks in person. I notice entirely different things about a place after drawing there for 5 hours, then I would if I just took a photo, and I hope others will as well.

BS: Coming from one of the most visited cities in Europe, your miniature paintings strongly remind me of the souvenirs targeting tourists. Are your hand-made, extremely personal vistas and your eco-friendly cycling habits a comment on this mass market economy and on unsustainable tourism?

DB: Not at all. It’s only my preferred method of travel, and of seeing the world, rather than a commentary

on the choices made by others. Honestly, I felt so lucky to be able to do this- cycle, camp in the forest, draw beautiful cities - that I barely

thought about the mass market economy, or politics, or tourism the entire time I was there.

BS: In pictorial terms, using oil paint on copper or on Plexiglas is the perfect combination to achieve glossy and very detailed images. How do you manage the transition from the isolated motifs you draw on paper to these badge-like and eerie realms?

DB: The sketchbooks are a sort of visual diary (as well as being my actual diary, since they end up covered in writing). The tiny copper paintings are rather distilled memories - I use the drawings and writing from the diaries along with photos I take during my travels to make them, and it usually takes a while for the image to crystallize.

BS: Cycling Guide to Lilliput was first displayed in New York with fifty of your round miniature paintings, all of which were numbered. How is your work this summer opening a new chapter in this series?

DB: I became pregnant with my son while finishing the first “Cycling Guide to Lilliput” series, and stopped painting for over a year after he was born. I always meant to finish the series, and now that he’s a bit older I have that chance. It’s the same series, but a new chapter- the way I paint has changed during the time I took away from painting, I have been doing a lot of thinking and drawing, and motherhood has changed the way that I approach art, which I feel is reflected in the work.

BS: On your website, you explain that painting is ‘an act of meditation’, which leads you to paint smaller and smaller pictures. How do you think miniature images affect both beholders and yourself?

DB: I believe miniatures have the capacity to draw a viewer into their tiny orbit - by being forced to look closely, I think people look with more attention. For me, there is a magic to creating a universe small enough to fit into the palm of your hand, I hope I can make others feel the same.

BS: You’ve studied at the Amsterdam Academy of Art, the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and the New York Academy of Art. Your Lilliputian views from Europe have been associated with American nineteenth-century landscapes, by Albert Bierstadt and George Inness for example. So how do you feel your work relates to European or American art?

DB: I have studied both American and European landscape painting in depths at various points of my art education and career- my work borrows strongly from both disciplines.

BS: Lastly, you mention on your website the complexity of exhibiting your miniature work to the public. Do you think Instagram has changed the way we see small-sized pictures or helped you overcome this practical issue?

DB: Absolutely. I’ve always painted miniatures, and always had a hard time finding a venue to display them until Instagram came along. I didn’t want to change the way I painted nor what I was painting, but Instagram made it possible to display the work to a larger audience than it ever had before, while allowing me to remain true to myself. I believe that it made it possible for people to discover art online and because people were doing it on their phones, and my paintings were already about the size of a phone image, it provided an audience for my tiny, impractical work.

If you liked this article and would like to stay up to date with our future publications then click here to subscribe to our mailing list!