Top 5 at The Other Art Fair London

Saatchi Art’s The Other Art Fair returns to London in October 5-7, 2017. There’s a plethora of abstract and figurative artists on show—although, the selection is somewhat weighted in favour of the former. From Elaine Kazimierczuk’s fragmented landscapes to Zeljka Paic’s architectural fantasies, Art Aesthetics chooses its Top 5 Artists to collect at The Other Art Fair 2017.

Elaine Kazimierczuk

Christchurch Meadow with Sunlit Hedge

Wolf Khan often says: ‘I’m painting paintings.’ Kazimierczuk similarly tells me, ‘I’m not painting landscapes, I’m painting paintings.’ Of course, they’re very different artists. However, they similarly work toward combining elements of landscape art with painterly abstraction. Khan’s works are more controlled than Kazimierczuk’s. I get the impression that the latter’s are composed of a thousand glances—from the scene to the canvas to the scene to the canvas. It’s as if they contradict one another yet remain authentic to their own glance and the resulting memory as it’s routed through the arms, hands, brush, and paint. Later, the same dynamic in the studio—from the newly printed source materials to the canvas to the photographs to the canvas. It’s wonderfully rare to grasp so concretely the intermediary position of the artist in her environment and works. It’s not just a canvas; rather, it’s a recording device that goes far beyond what any camera can imagine. Kazimierczuk urgently writes that she uses ‘selective vision, selecting elements from the array of visual patterns before me and turning these into my own idiosyncratic motifs.’

She quickly follows this with: ‘[a]s I’ve grown in confidence, my work has grown in size.’ She wasn’t always encouraged to pursue the arts in which she’s so obviously at home. She regrets grammar school: ‘I was actually forbidden to take art—shunted off in an academic direction—art was neither encouraged nor supported as a viable career choice.’ If only her teachers could see these paintings now! They’re bold. They’re spontaneous. They’re enthusiastic. Even, charismatic. Kazimierczuk says she’s trying to give her viewers ‘an immersive experience’ and this is certainly true—you can get lost in these paintings whether they’re huge diptychs or singe, smaller works: you can survey the figurative landscape, or you can focus on the abstract paintings that collectively form the image. Kazimierczuk reflects for a moment: ‘all painting is abstract in a sense; painters abstract elements of colour, light and energy from the interplay of patterns before them.’ she clearly, then, thinks about what she’s doing. She’s ‘switched-on’ about being an artist. It’s worth recalling that she’s only been painting for three years. In 2016, she was shortlisted for the BP National Portrait Award. She sells. She’s certainly one to buy. And watch.

Zeljka Paic

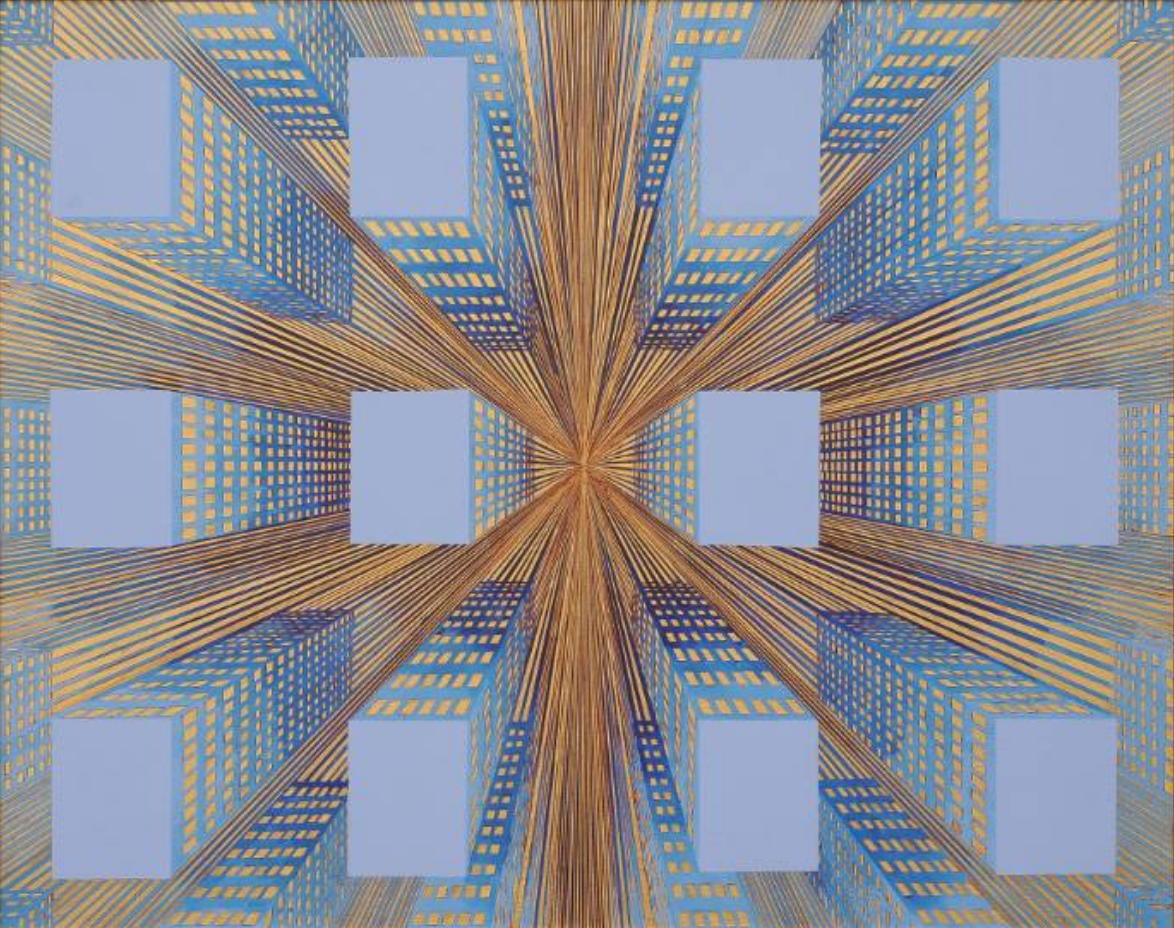

‘I grew up in a family of mathematicians, economists, and engineers,’ says Zeljika Paic. ‘I was the only artist.’ However, ‘their influence was inevitable and I went to a school where maths was the main subject.’ Paic attended Banja Luka’s Faculty of Architecture and Civil Engineering and then enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts before emerging with the ‘Golden Award’ for best student in 2015. Paic learnt ‘linear and axonometric perspective’ from the former and ‘aerial perspective and gradient’ from the latter. She’s an ingenious mix of sciences and arts. She pairs the word ‘imagination’ with ‘reason’ when she writes to me about symmetry. She also declares that there are always ‘some rules in aesthetics. For example, green and red are complementary, they were and they always will be.’ Her adherence to the Red-Yellow-Blue Colour Model (RYB) suggests the same artistic sensibility paired with the exacting approach of the sciences.

Paic’s Other Perspective (2017) and Development (2017) toy with the same dichotomy of her formative years at the Faculty and Academy. They ask the viewer to think more about the meaning of ‘perspective’ and ‘development’ in their humanities and sciences’ contexts. Development might be a road or flower’s petals just as ‘development’ might mean an architectural construction or natural growth. Other Perspective suggests an optical illusion: there are twelve bluish rectangles floating in space; or, a modernist vision of the metropolis with its perspectival lines extended ad infinitum while glowing as if to form an electric star at the centre of the canvas. Or, perhaps it’s a cross? Or, perhaps it’s just the windows turning into the cables that convey the power to the lighting therein? Her works exude material quality just as the luxurious golds and blues intimate an ikon. Indeed, they suggest all of the above.

Alan McLeod

Shield Orange (2017)

There’s a shop-front on Columbia Road where they’ve stripped away the paint revealing layer upon layer of colour—enough to rival the famous flower market that takes place there every Sunday. McLeod’s Shield (2017) doesn’t excavate this sort of half-forgotten past. Instead, it imagines a past in the application of layer upon layer of gouache and metal-leaf. It’s not there to be re-discovered; rather, it’s artificially and artistically built up over hours of the artist’s own time. Shield is therefore described as an ‘[i]magined artifact’ or ‘ancient sun disc’. It reimagines the very concept of the antiquity in a vein of myth with romanticism. McLeod’s ‘ancient sun disc’ suggests that we’re gazing at the forbear of someone or other’s saintly halo. His Shield seems to occupy the same space as Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘Ozymandias’ (1818) or Sigmund Freud’s Moses and Monotheism (1939) in that they similarly imagine—even, fantasise—an object from an antique land. McLeod’s faux-antiquity also intimates what’s been lost ‘after the plundering, years of neglect and souvenir hunting,’ and reminds us that ‘all that remains are fragments of architectural and decorative surfaces.’

We’re not to wonder, then, whether Freud was correct when he wrote that Amenhotep IV (a.k.a., Akhenaton or Ikhnaton) ‘worshipped the sun not as a material object, but as a symbol of a Divine Being whose energy was manifested in his rays.’[1] Or, when he scandalously suggested that the sun-god Aton is Adonai: ‘Hear, oh Israel, our god Aton (Adonai) is the only God.’[2] Or, when he argued that monotheism was born of a cult of the sun and that the founder of Judaism wasn’t a Jew rather than an Egyptian. Instead, we’re left with just an abstract painting that intimates all of the above without recognising it. Instead, it’s simply there in its abstract and enigmatic given-ness. It’s this that gives it its alluring, beautiful quality.

Karen Wood

Karen Wood isn’t just an ‘artist’ but an ‘urban explorer’ who conjures art out of the mundane road markings that we abide by—without ever properly seeing—every day. Sam Jacob of the University of Illinois at Chicago and visiting professor at Yale University recently wrote for Dezeen that ‘[r]oads are super complex landscapes. All those speed bumps, arrows, double yellows, zig zags, kerbs, red men, green men, zebra, pelican, puffin and pegasus crossings are both the surface over which we travel and codes that modify and instruct how we travel. They are simultaneously map and territory, abstract markings on the surface of the city that become the city.’[3] Wood’s Back to the Road (2017) abstracts such road-markings from their “natural” environment. They’re cut-out into modernist works of art. It’s as if they’re inspired by the cut-outs and découpage of Matisse or the De Stijl of Mondrian. Interestingly, the latter is often referred to a neoplasticism and road markings are similarly made with thermoplastic paint in bright colours along predominantly straight edges. It’s interesting, then, to witness the coincidence of the high-brow and the lowly infrastructure of the world in which it all takes place.

Wood’s artworks explore these super complex landscapes in which we live and, especially, the ways in which we’re allowed to move through them. David Harvey’s excursus on Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s renovation of Paris in ‘The Right to the City’ (2008) states that Haussmann ‘created an urban form where it was believed—incorrectly, as it turned out in 1871—that sufficient levels of surveillance and military control could be attained to ensure that revolutionary movements would easily be brought to heel.’[4] Haussmann sought to control the same city that the flâneur sought to explore. Merlin Coverley’s Psychogeography (2006) states that ‘[l]ike London before it, Paris in the nineteenth century had expanded to the point where it could no longer be comprehended in its entirety. It had become increasingly alien to its own inhabitants, a strange and newly exotic place…characterised as a jungle, uncharted and unexplored, a virgin wilderness populated by savages demonstrating strange customs and practices.’[5] It’s worth reconsidering the struggle between control (of movement, traffic, etc.) and urban exploration in contemporary London. We’re constantly moving through space. We’re constantly exploring the city. We’re constantly curtailed by the directions for movement therein.

Way Through (2017)

Attila Kotányi and Raoul Vaneigem’s ‘Basic Program of the Bureau of Unitary Urbanism’ (1961) stated that their first task was ‘to enable people to stop identifying with their surroundings and with model patterns of behaviour…We must encourage their scepticism toward those spacious and brightly coloured kindergartens,’[6] for ‘[o]nly a mass awakening will pose the question of a conscious construction of the urban environment.’[7] Wood similarly suggests that the colours of ‘controlling signage’ might be described as the ‘hyperreal’ as described by Jean Baudrillard who’s work shares much in common with that of Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (1967) and the other members of the Situationist International as Kotányi and Vaneigem. Wood’s Way Through (2017) is in much the same vein of critical and artistic thought in that it distils the experience of walking the city into white, black, and blue. It’s a really pristine reduction of the cacophony of the city into one of its purer forms—not through the eyes or artist’s vision, but through the actual movement of the body through the built environment. Furthermore, someone who collects these artworks collects a part of our contemporary moment: more people live in cities than the countryside for the first time in our history. From gentrification to Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS), the city is increasingly subject to new political and aesthetic visions. Wood successfully intervenes in these contemporary debates.

Vesna Milinkovic

It’s easy to underestimate exactly what it takes to do abstract art. Of course, most critics can’t underestimate this given our usual standing as failed artists. We’re (for the most part) unskilled with any paint brush—though, not for want of trying—and instead settle for criticism. I wonder whether overly critical criticism is just a proxy for the critic’s own failures… I can only say, then, that Vesna Milinkovic does abstract art as I can only have wished to have done. Milinkovic tells me that ‘[c]ombining the lyrical with the geometric is a metaphor’ for ‘the struggle between order and freedom.’ She’s incredibly erudite. We’re often born into a predetermined place in this world. Our names are chosen and inscribed well before we’re born—perhaps, before we’re even the dimmest twinkle in our parents’ eyes. Nonetheless, we’ve all got to find our own breathing space and freedom in the society and culture in which we find ourselves. Or, as Milinkovic puts it, ‘we each to varying degrees seek to break out and find our own way to express something from the soul…perhaps, this is a clue to our ultimate human purpose.’

Milinkovic’s musical tastes intimate the same struggle. She enjoys listening to Tibor Szemző’s Wasser Wunder (1982) as performed by the Hungarian ensemble, Group 180. ‘[F]or me, it defines an approach to contemporary abstract painting, simultaneously lyrical and structured.’ We’re accustomed to the concept of deconstruction wherein there's something or was something to be deconstructed. Wasser Wunder proceeds in the opposite direction, it’s begins with its fragmentary and deconstructed parts—often, single notes played as if they were being read at different tempos—before coming together into something that sounds rather like classical music. Crucially, this isn’t the same as simple construction—when you start with a black canvas and go on from there. No, the construction is already there in its fragmentary pieces. It’s of the futur antérieur or future perfect. I’m tempted, then, to consider her Into the Light (2017) as the same future perfect of Composition 8914 (2016). It’s as if the first mark on the canvas could have gone in either direction. Each mark is a road travelled. Choices made. Struggles undertaken.

For every mark upon the canvas is, in a way, meaningless, until you’ve arrived at the finished piece—or at least, until you or someone else decides that it’s finished. And yet, it’s only with this finished piece in mind that the first mark is made. Milinkovic’s paintings evoke the same themes in their dialectic of structure and freedom. In a way, its place is already marked out and the process of painting seeks to arrive at that place. Milinkovic’s prodigious output is almost a testimony to this remarkably human process.

The Other Art Fair runs from 5-8th October at the Old Truman Brewary, London. Click here for more information.

[1] Freud, Moses and Monotheism, trans. by Katherine Jones, (London: Hogarth press, 1939), p.37

[2] Freud, Moses and Monotheism, trans. by Katherine Jones, (London: Hogarth press, 1939), p.42

[3] Sam Jacob, ‘It’s time to refigure the design problem of the London street’, Dezeen 2013, https://www.dezeen.com/2013/11/18/opinion-sam-jacob-cycling-road-design/

[4] David Harvey, ‘The Right to the City’, New Left Review, No.53, September-October, 2008, https://newleftreview.org/II/53/david-harvey-the-right-to-the-city

[5] Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography, http://portfolio.newschool.edu/guydebord/files/2014/09/Merlin-Coverley-Psychogeography-The-Flaneur-1zziocc.pdf

[6] Attila Kotányi, Raoul Vaneigem’s ‘Basic Program of the Bureau of Unitary Urbanism’ (1961) http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/6.unitaryurb.htm

[7] Attila Kotányi, Raoul Vaneigem’s ‘Basic Program of the Bureau of Unitary Urbanism’ (1961) http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/6.unitaryurb.htm