The Rise Art Prize

Rise Art offers the public the opportunity to vote for the winner of the Rise Art People's Choice Award, 2018. They’ve just announced the finalists. We’ve picked out our favourite five—or rather, six—artists from the shortlist. The finalists have been chosen by a team of ‘insiders’ from all over the art world. They include curators such as Rachael Thomas of the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) and Sarah Martin of the Turner Contemporary in Margate; journalists and editors such as Emily Tobin of House and Garden and Beatrice Hodgkin of The Financial Times’ How to Spend It supplement; academics like Jean Wainwright of the University for the Creative Arts (UCA) and, of course, artists such as Anthony Micallef and Bruce Mclean.

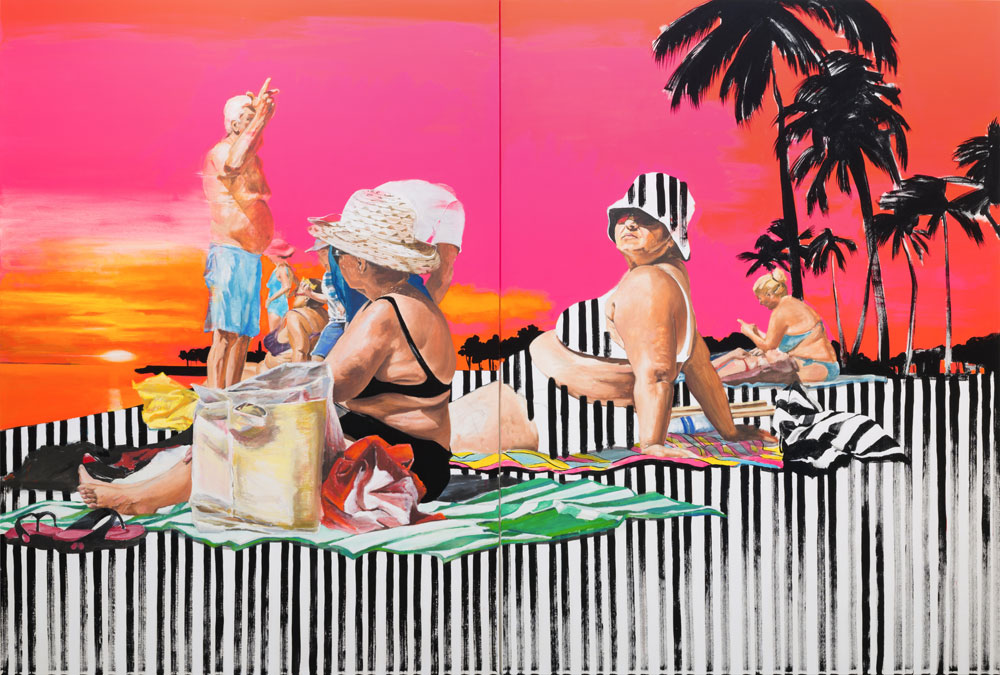

Stella Kapezanou - Europe

Stella Kapezanou works mainly in Greece and the United Kingdom. She’s looking forward to 2018 having won the Clyde & Co Emerging Star Award last year. Her works aren’t just visually, but conceptually appealing. Perhaps ironically, this makes her paintings worth far more than their gallery price.

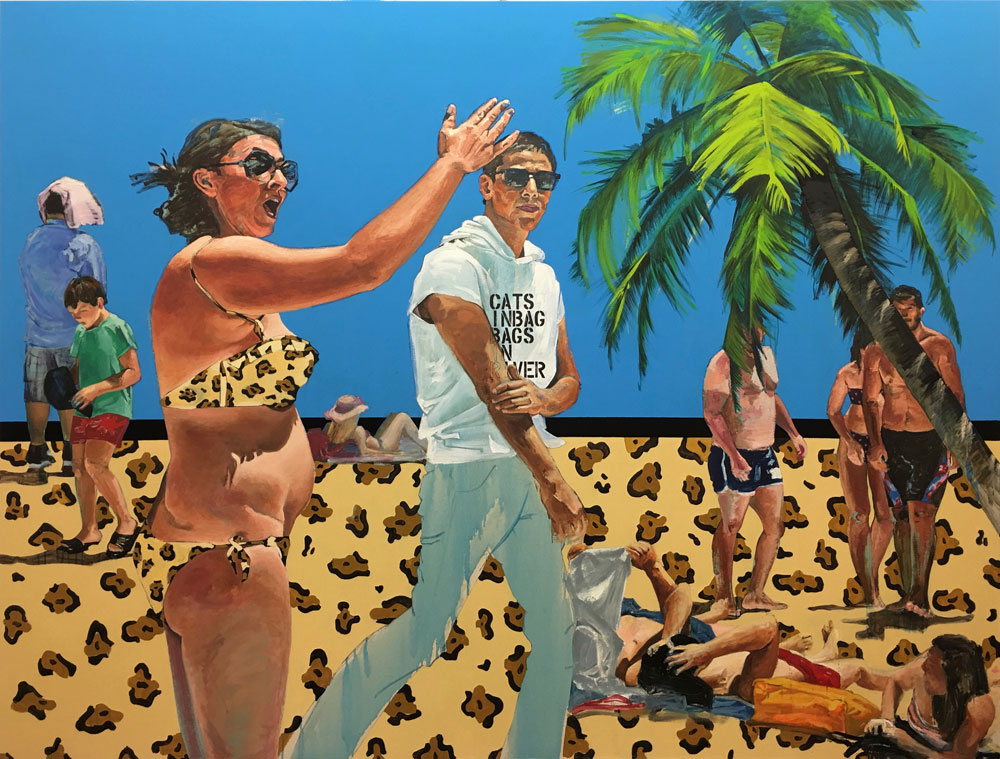

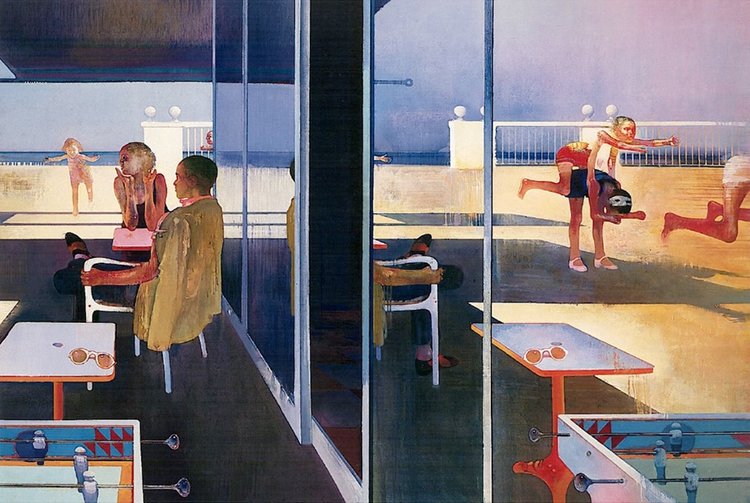

Kapezanou’s From Heavens with Love (2016) and Cats in Bags (2015) along with Heavens (2015) bring to mind Leonardo Cremonini’s Obstacles, Parcours et Reflets (1975-76) and Les écrans du soleil (1967-68) or even Les plafonds de la plage (1968). Why? It’s not because they’re just paintings of people, or, more specifically, people lazing about on the beach. For this interpretation falls into the very ‘aesthetics of consumption’ criticised by Kapezanou as Louis Althusser’s ‘Cremonini, Painter of the Abstract’ (1966) had criticised over fifty years ago: ‘Cremonini 'paints' the relations which bind the objects, places and times.’ He’s a ‘painter of abstraction. Not an abstract painter…but a painter of the real abstract, 'painting' in a sense we have to define, real relations (as relations they are necessarily abstract) between 'men' and their 'things', or rather, to give the term its stronger sense, between 'things' and their 'men'.’ So, what’s changed since Althusser and Cremonini? Or, why Kapezanou?

The answer is that it's too picture perfect: the perfect sunset juxtaposed (in non-relation) with the white glare of flash photography on the bodies of the painting’s subjects. They're almost adverts, unrelated possibilities in the same frame of the painting. And, of course, the bar code that runs through the sands and makes the entire beach experience a mere purchase... Cats in Bags is similarly disjointed. There’s hardly, then, a human drama in any of the paintings. If so, then what does Kapezanou paint? She paints the very absence of relations, she paints the very opposite of, say, Bernardo Siciliano’s The Social Network (2017). Kapezanou’s subjects don’t intersect. They’re just strange people playing in a fake world. For life’s a beach; without the depth of the ocean in sight.

Tom Waugh - UK

Waugh’s sculptures of boxes are ‘squashed’, ‘crushed’, or ‘stuffed’. It’s fitting that the adjectives are metaphors—however evasively, idiomatic—for death itself. For it’s not just rosemary, but marble that’s for remembrance. Similarly, what is set or ‘carved in stone’ cannot be undone. Pope Urban VIII sought this same immortality through Bernini just as the di Medicis had through Michelangelo. It’s interesting, perhaps, that Waugh’s sculptures share something with that of Urban VII: Michelangelo’s sculptures of the di Medicis are stylised and heroic; Bernini’s Urban VII isn’t yet agéd, but no longer youthful yet more true to life. Similarly, these boxes have already begun their journey of decay and, once unpacked, are probably ready to be thrown away. Waugh’s Bag for Life (2017) rams this point, bitterly, home. It's uncanny, then, that the carrier bag’s folds intimate the drapery of an ancient toga...

It’s not always the case, however, that marble, stone, and ivory serve only those who have passed; but also those who are yet to come. Ovid’s Metamorphosis (8 AD) recounts the story of Pygmalion, who prayed to Venus that one of his works be brought to life:

‘Si Di dare cuneta potestis : Sit conjux opto, non ausus, eburnea virgo,

'Dicere Pygmalion, similis mea dixit, eburnae.’

‘If, O ye gods, all things are in your power, let my wife (not daring to say this ivory maiden) resemble this ivory statue.’

Venus heard Pygmalion and brought the statue to life. Waugh’s sculptures carry an important environmental message: jerry cans, cigarette butts, plastic cups, and cardboard boxes. Let’s hope that this message can be brought to life, and these ephemera, which signify the gratuitous wastefulness of the present, similarly passed into history and therefore truly commemorated as the past.

Lebohang Kganye - Middle East and Africa

Lebohang Kganye works in Johannesburg, South Africa. She recently won the Jury Prize at the Bamako Encounters Biennale of African Photography in 2015 and the CAP Prize in Basel, 2016. She also received the Sasol New Signatures Competition in 2017. The Walther Collection, Ulm, and Carnegie Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, have recognised her talent and her works now form part of the museums’ collections.

Kganye’s works are small stages or sets, miniature ensembles of family history that are then re-photographed and re-framed. However, the family album cut-outs are often as blurry as they are sharp and sometimes, they’re just silhouettes. We’re aware that these are stories-told and stories yet untold. They’re stories, perhaps, that might never be told, only imagined and then re-imagined.

Touria El Glaoui, one of Rise Art’s ‘insiders’ and the daughter of the famous Moroccan artist, Hassan El Glaoui, says that Kganye ‘distorts the linearity of time by exploring how history, memory and nostalgia can be altered, reshaped and rewritten,’ by ‘re-enacting past moments and inserting herself into these narratives in the present.’ She therefore achieves ‘a real reimagining of what the 'family portrait’ can be and the numerous ways in which one can document lived experiences.’

Salman Rushdie’s Midnights Children (1980) similarly explores the same strange inconsistencies of family—indeed, even national—history, through the reflexive ordering of the past by the present, and, therefore, the present by the past. Unlike Kganye’s photograph albums, Saleem, the writer-narrator, uses gastronomic metaphors (which are also olfactory, his nose is said to be famously large) to symbolise the strange concoction that is history. He writes that ‘[r]ising from my pages comes the unmistakable whiff of chutney.’ His long-suffering Padma asks him to hurry up and tell the story, ‘bullying me back into the world of linear narrative, the universe of what happened yet.’ But, says Saleem, ‘[t]hings—even people—have a way of leaking into each other’. Similarly, Kganye says that ‘[t]he more I researched my family history, it becomes apparent that family history remains a space of contradictions, it is a mixture of truth and fiction.’ She suggests that these are stories ‘which are told in multiple ways, even by the same person—memory combined with fantasy.’ It’s this strange mixture that’s of striking prominence today. And Kganye, she’s one of the best for exploring this strange and fraught place of memory, fiction, history, and contemporary personhood.

Elizabeth Waggett - Americas

Elizabeth Waggett’s drawings are superbly accomplished. She then applies a thin layer of gold leaf to finish the work. In this way, she presents a challenge to the viewer to re-think the concept of ‘value’ as presented in the artwork and the wider world.

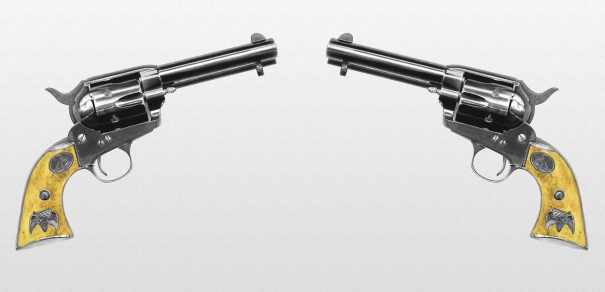

Manifest Destiny-The Peacemaker (2016) reminds me of the images that circulated around the world in October, 2011. Col. Gaddafi had just been killed and a young seventeen year old, Mohammed Elbibi, was waving the old dictator’s gold-plated Browning 9mm. It’s something about the conjunction of money and violence in the same object that’s so brazen and thus unsettling. Waggett’s Skull 2 might remind you of Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God (2007) but it’s closer to Medieval theology in its bare skull with the gold crown of thorns, the earth-bound reliquary of a halo. The Curse of Being Magnificent (2017) is particularly neat, it depicts a lobster, which is a delicacy, of course, with a gold elastic band trapping its claws. You’re aware that she’s trapped by her own finery, her own deliciousness, her own wealth.

Waggett wants to draw attention to ‘value’ in the modern world. It’s acknowledged that ‘art’ proves the exception to the Labour Theory of Value. It’s not a question of working hours, days, or even years… David Graeber presents a plausible theory that the advent of gold/money as a universal equivalent begot two categories of value: that which could be exchanged; and that which could not. You can’t compare, say, love, which cannot be exchanged, with the simple commodity. It’s no mere coincidence that a peculiarly modern form of love arose at the same time the very category of aesthetics and, actually, alongside capitalism. For they’re the obverse of the latter’s emergence. You can’t truly compare one painting’s value with another, yet there is this other ‘value’ measured in currency that attempts exactly that. It’s this duality that can't help but attend most, if not every, artwork. For this reason, Waggett’s works are a challenge to the artist, critic, collector, and curator. She slaps this universal equivalent straight onto the objet itself. It’s an affront, yet it’s value too. You can’t pretend this hypocrisy isn’t there and that we’re all, desperately, caught in it.

Lee Yuan Ching & Lei Sylviye - Australasia

Lee Yuan Ching Meditation 5 (2016)

Lee Yuan Ching learnt watercolours and calligraphy from his father. Ching was born in Taiwan, the Republic of China rather than the People’s Republic. But this didn’t stop Hu Jintao, the president or ‘paramount leader’ of China (2002-12) from collecting Ching’s works in 2007. We’re also enamoured with Lei Sylviye’s ethereal abstract paintings. Sylviye, like Ching, was born into a family of artists. Unlike Ching, Sylviye was born in Macau, an autonomous region of the People’s Republic of China. Ching and Sylviye’s works are poles apart: Ching’s inkworks appear thoroughly contemporary, but reference techniques practiced throughout China for millennia. Sylviye’s works are incredibly futuristic, they’re almost imagined renderings of cyberspace. We’ve recently written on the rise of Asian artists and collectors. We’re lucky, then, that Rise Art offers us the chance to invest in one of the fastest growing, creative, and lucrative pars of the art world today.

Lei Sylviye Dimensional sequence 2017-4 (2017)

Sylviye begins with geometric shapes, each form returns with diminishing saturation as they turn to white. They’re almost the shadows and penumbras of an electric light mechanically repeating themselves with minor variation into the distance. Sylviye is playing with rendering augmented or virtual reality, those strange otherworldly places that, in these paintings, offer us glimpses into the purest electric white. On the other hand, Ching’s works are mesmerising, swirling dances of colour. You’re tempted to espy an array of figures, shapes, and objects. They might be curls of smoke or organic, leafy tendrils. They might be immiscible liquids like oil and water, but they’re actually plumes of ink intimating all manner of fantastic creatures. You can get lost in these artworks. His Meditation 5 (2016) is simply blue, red, black, and white. There’s the unmistakable flat-plane effect characteristic of so much Asian art. In Meditation 6 (2016) there are so many shades of grey, the gentle dilution of the once black ink. The work offers more visual depth accordingly. We couldn’t choose between these artists that are poles apart.