Ali Nedaei's Silent Myths

Ali Nedaei, whose works have already graced galleries in Tokyo, Paris, and Venice, is preparing for his first solo-exhibition in the UK at CAMA Gallery, London. He’s already appeared in the gallery’s inaugural exhibition which showcased some twenty-one Iranian artists, Sensation (5 Apr. – 25 Jun., 2018). Replete with poetic allusions but masterfully executed, Nedaei’s works are surprisingly accessible—even for those who are unfamiliar with Iranian culture.

Considering the oral origin of most cultures’ myths, the title of the exhibition, Silent Myths, seems somewhat tongue-in-cheek. But, it’s apt. Moving from Tehran to London, the works will have to cross both language and cultural barriers to engage with their new British audience. Silent Myths poses the question: what commonality do our myths have?

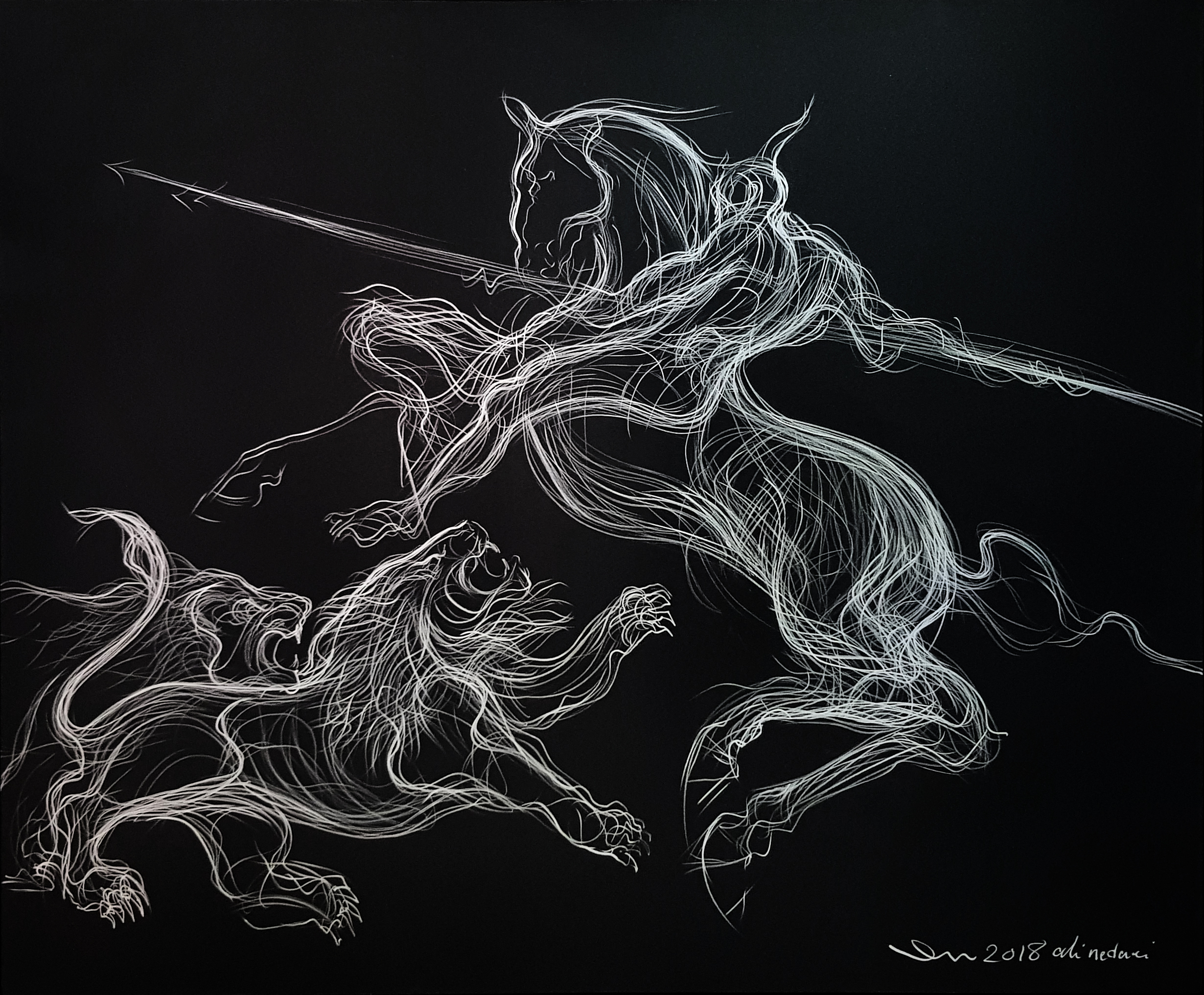

Ali Nedaei's The Battle of Lion and Myth No. 1 (2018)

Nedaei’s work avoids referencing specific narratives in favour of exploring a broader concept of myth. The Battle of Lion and Myth No.1 and No.2 (both 2018) are currently on display as part of CAMA gallery’s Sensation. The central figure of both canvases, the mounted warrior, is never identified. As viewers, everything we know about him is confined to this one battle against lions. In Iran, hunting lions has long been seen as a pastime of kings, and as such the feat has been ascribed to many. Heroes such as Esfandiyār and Khusraw Parvēz both defeated lions and thus demonstrate their right to rule and ‘farr’. Found in Persian poetry, ‘farr’ is most commonly translated as glory, but has more subtle connotations of a heavenly splendour and luminosity.[1] It appears throughout Ferdowsi’s epic poem, the Shahnameh (c., 1000 CE), which traces the succession of kings from Iran’s mythic origins into documented history. The qualities of a good ruler are its central theme.

Perhaps the most direct demonstration of the link between the quality of ‘farr’ and battling lions and is the tale of the Sasanian king Bahram Gur. After his father’s death, Prince Bahram returns to his kingdom only to find a pretender, Khosrow, on the throne. To settle the matter of succession, Bahram Gur suggests they compete to retrieve the crown from between two lions; the first to successfully slay the lions would become the new Shah of Iran. This unusual proposal prompts a discussion in the poem between the priests and nobles of the court.

'He possesses the divine farr… He speaks about nothing but justice and we should rejoice in this. And as for his talk of wild lions and placing the crown and throne between them… if he does gain the crown, his glory will surpass Feraydun’s.'[2]

The courtier’s statement suggests a link between nobility, physical prowess and justice which is reinforced only a page later. Faced with the lions, Khosrow withdraws from the contest, aptly summarising the ideal traits of a ruler in the process.

'Only a prince ambitious for renown

Deserves to reign and to possess the crown;

And then I’m old, while he is young and strong

I can’t fight lions’ claws, I’ve lived too long.

Let him display his prowess, let us see

His youth and health enjoy their victory.'[3]

Bahram is ultimately successful, taking the crown and with it the title of Shah. This myth remains popular in Iran today, and the Shahnameh continues to have a wide appeal. It speaks to the fact that a ruler’s ability to protect still has currency in today’s world.

However, the association of feats of strength and the ability to dispense justice are not unique to Iranian culture. If you’ve ever seen the Assyrian Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal, currently in the British Museum, then you’ll immediately recognise the strange potency with which such imagery has travelled across ancient and contemporary cultures of the Middle East. But perhaps what is truly surprising, is the consistency of the imagery, not just over time, but across the globe. For viewer’s familiar with western art history, the rearing horse of The Battle of Lion and Myth No.1 may recall Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801) whose subject remains one of France’s greatest myth. Both images exaggerate the horses’ musculature, captured mid-action, to convey an untamed energy that emphasises the rider’s control.

Ali Nedaei's The Battle of Lion and Myth No.2 (2018)

But it works because Nedaei has been selective in what he adopts from the French academic tradition and merges it with an experimental medium to create an image that is undeniably contemporary. Nedaei’s use of a marker pen rather than paints, allows the images to be built up through a plethora of lines, giving a spontaneity to the works that is rarely seen outside of preliminary sketches. The light but sure marks of the horse’s rear leg in No.2, show the debt the work owes to the techniques of life drawing. Nedaei seems able to accurately model a limb in just a few strokes, and his slight variations in pressure give the lines an almost calligraphic quality.

In drawing from numerous disciplines and visual sources, Nedaei’s work transcends cultural borders in much the same manner as the ideals of myths. Like the multiple lines of the image, viewer’s different cultural backgrounds foster many interpretations of the subject that diverge, conflict, and overlap. Yet, overwhelmingly, you’re left with the impression that there is far more that unites than separates the cultures on which Nedaei draws.

Silent Myths runs from 3 July - 2 Aug., at CAMA Gallery, London.

[1] http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/farrah

[2] Abolqasem Ferdowsi, Shahnameh, Vol. III, trans., by Dick Davis, (Washington: Mage Publishers, 2004), p.230.

[3] Ibid., p.233.