The Masculine

Defining what it means to be a ‘man’ in Iran is a deceptively complex task. Models for manhood, emerging from history, religion and pop culture, from Cyrus the Great, via Imam ‘Ali, to literary hero Rostam and Olympic wrestler Gholameza Takhti, present a stoic mind combined with a body of sublime muscularity; a paradigm that runs uninterrupted from ancient king to prophet to pahlevan (the Persian term for ‘strongman’). But the reality of Iranian manhood hasn’t always been that straightforward. There is an artistic and poetic heritage away from these hypermasculine idols; medieval verses dedicated handsome young wine bearers (saqi) described as being ‘moon faced and of cypress waist’, monumental renderings of eighteenth-century shahs in high heeled shoes and dripping in pearls. A sense of what we might term ‘feminine’ was never far away, but it has not been something that has always been placed in opposition with a sense of manliness. It wasn’t until a more modern polarisation, tumbling through from the 1850s, through the turbulence of the Pahlavi’s, into a post ‘79 reality that notions of gender and sexuality began to ossify itself into strict binaries in the Persian imagination. The outrageously elegant and ostentatiously camp appearance of Fath ‘Ali Shah, second king of the ill-fêtedQajar dynasty, translated into an unshakable image of power in the early 1800s. However, some two-hundred years later, bedecked in neon velvet leotards and scattered with sequins, although beloved by the public, the flamboyance of dance instructor Mohammad Khordadian only raised suspicion with authorities. Iran’s artists, be they state-sponsored, in exile, part of the diaspora, or working under the radar, have been witness to the various tectonic shifts in the country’s attitudes to self and sex.

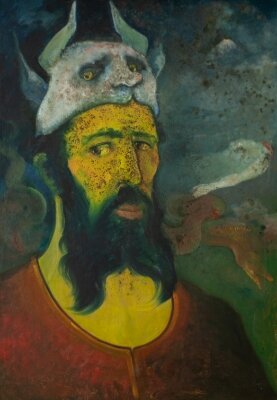

Bahman Mohasses, Minotauro (1966)

Bahman Mohasses (1931 - 2010) was the bad boy, the pesar-e bad, of Iran’s contemporary art scene since the 1950s. He was dubbed, of course, by virtue of this reputation as ‘the Picasso of Iran’ by European art critics searching for a familiar moniker on which to hook his work for a home audience. Mohasses’s life was a mixture of artistic genius and sexual tumult that may seem similar, at least on the surface, to art’s most notorious matador, but it was an entirely different story in reality. Both men, however, were entranced by the figure of the Minotaur. Perennially associated with sex and death, the symbol of mythic power was subverted by Picasso into cowering heaps, pierced with as many arrows as Saint Sebastian. Its various appearances, lying beside row boats, or stumbling around corners by candlelight was an ode to machismo that had more in common with the lion and the bees, a biblical motif that now adorns pantry-bound cans of Golden Syrup: out of the strong came forth sweetness. Mohasses’s Minotauro (1966) has flaked and rusting flesh, but this ultimately peels away at the body of a steely eyed and crossed-armed pahlevan. The beast is the boss at the end of a fairy tale mission, not unfeasibly appearing as a homoerotic villain conceived in the mind’s eye of a Chuck Tingle porn satire. The Minotaur is a sex god. Out of the strong came something else entirely.

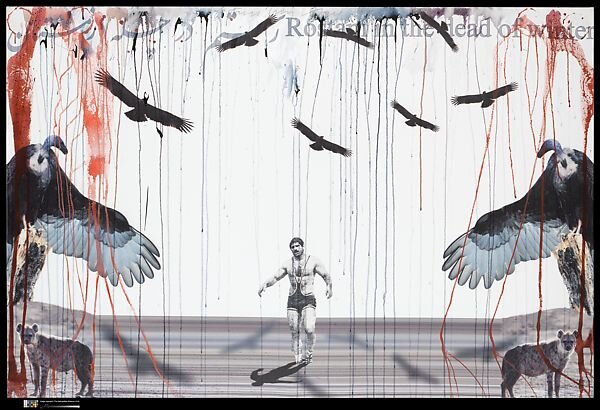

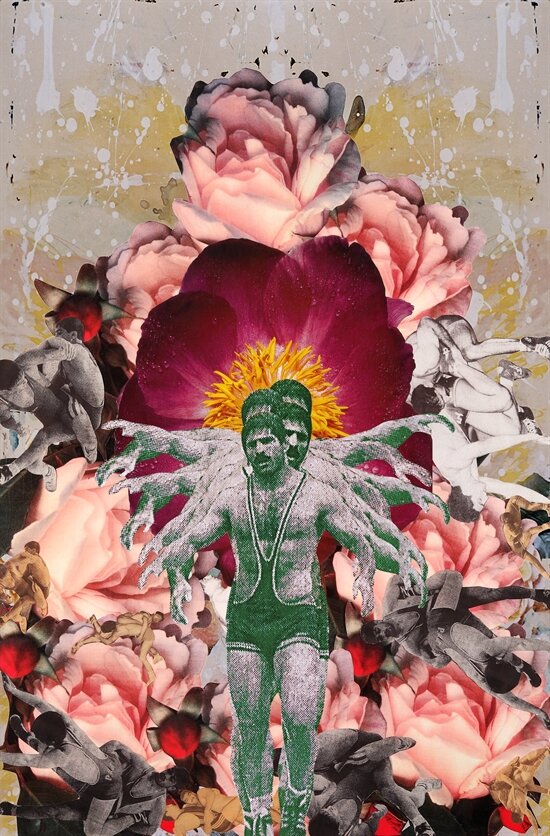

The pahlevan is conjured too by Fereydoun Ave (b. 1945). As part of his now iconic Rostam series of works centred around the legendary hero of Ferdowsi’s eleventh-century national epic Shahnameh (Book of Kings), the figure of this ‘champion of champions’ is reimagined as a moustachioed wrestler. Mimicking the Herculean trials of his namesake, the man wades through imagined environments built from mixed-media collage, chased by crows and wolves, rained-on from above by Twombly-esque drips of paint (indeed, the two artists were friends and collaborators). Ave’s work explores all the nuances of Iranian masculinity – both strength and sensitivity – via the conventions of classical poetry, prose and painting. The seventeenth century masterpiece Shah Abbas and his Pageboy, attributed to the Safavid-era artist Muhammad Qasim, was the inspiration behind Ave’s eponymous series, weaved from textile fragments acquired from Tehran’s winding bazaars. Entirely abstract, the connection between Ave’s patchwork lahaf quilts and Qasim’s painting is conceptual rather than literal. Where we can’t see the elegant but charged embrace between the Shah and his youthful serving boy, our minds are instead transported by the swathes of fabric to the sensuality of the scene itself; a congress between lovers on a freshly spread picnic rug, the undulating folds of rucked up robes, hastily undone waistcoats, unravelling turbans.

Entirely unclothed, Tara Khoshneshin (b.1981) cast a male torso in plaster and adorned it with Persian roses (Untitled – 2015). Its companion piece is the female equivalent, set against a red background instead of a glossy black. It is part Greek statuary, part Qajar enamel. The Apollo Belvedere mixed with the romance and camp of a Jean Paul Gaultier cologne bottle. Other boy’s toys have received the same lacquered treatment by the artist: vintage model cars and two wooden airplanes. The talismans of the journey from Persian boyhood to manhood, decorated by Khoshneshin with delicately rendered twisting stalks of antique blooms extends, more menacingly, to a rifle. Apparently from composite parts, the gun is stripped of its efficacy and borders on a plaything rather than a killer technology (it reads more like an air rifle, the stock apparently too slim). Nevertheless, in its symbolism this is a statement that goes beyond sweetening toughness, more than just creating a stark dichotomy between petal and trigger or tempering the brawn of Rostam with the traditions of gol-o-bolbol (flower and nightingale). Emerging from the rubble of the Revolution as the 1980s began, Iran went to war with Iraq; a bloody conflict that resulted in the tragic deaths of an estimated 500,000 men on both sides. For Iran, it was the loss of a generation of sons and husbands. The martyred thousands are commemorated with flowers as red as the bloodshed: in cemeteries stacked with graves, in murals at the roadsides and emblazoned on the side of buildings. Khoshneshin applies the aesthetics of mourning to the instrument of war.

Nearly the entire roster of protagonists from the Shahnameh whizz across the surface of Khoshneshin’s mixed media canvases, busy with defeating monstrous demon foes (div), brandishing daggers and spears with a concentrated intensity. The stretched, blurred effect which wipes out half of the composition in a sweep of movement only serves to increase a sense of the impressive physicality and daring-do of these mythical men. The artist also turned her hand to depicting the succession of Qajar kings, who ruled Iran with varying degrees of success over a long century from 1789 to 1925. Her renderings are just as unstable and fluctuating as establishing a sense of manhood was during this period, when pre-existing - and less binary - impressions of maleness were the subject of European derision and an embarrasing sense of national self-consciousness as modernity beckoned. Images of the Qajar shahs, bedecked in their imperial finery, ripple and wane with an entirely different effect to Koshneshin’s storybook heroes: their impermanence is not masculine strength and fury, but indulgence and ineptitude.

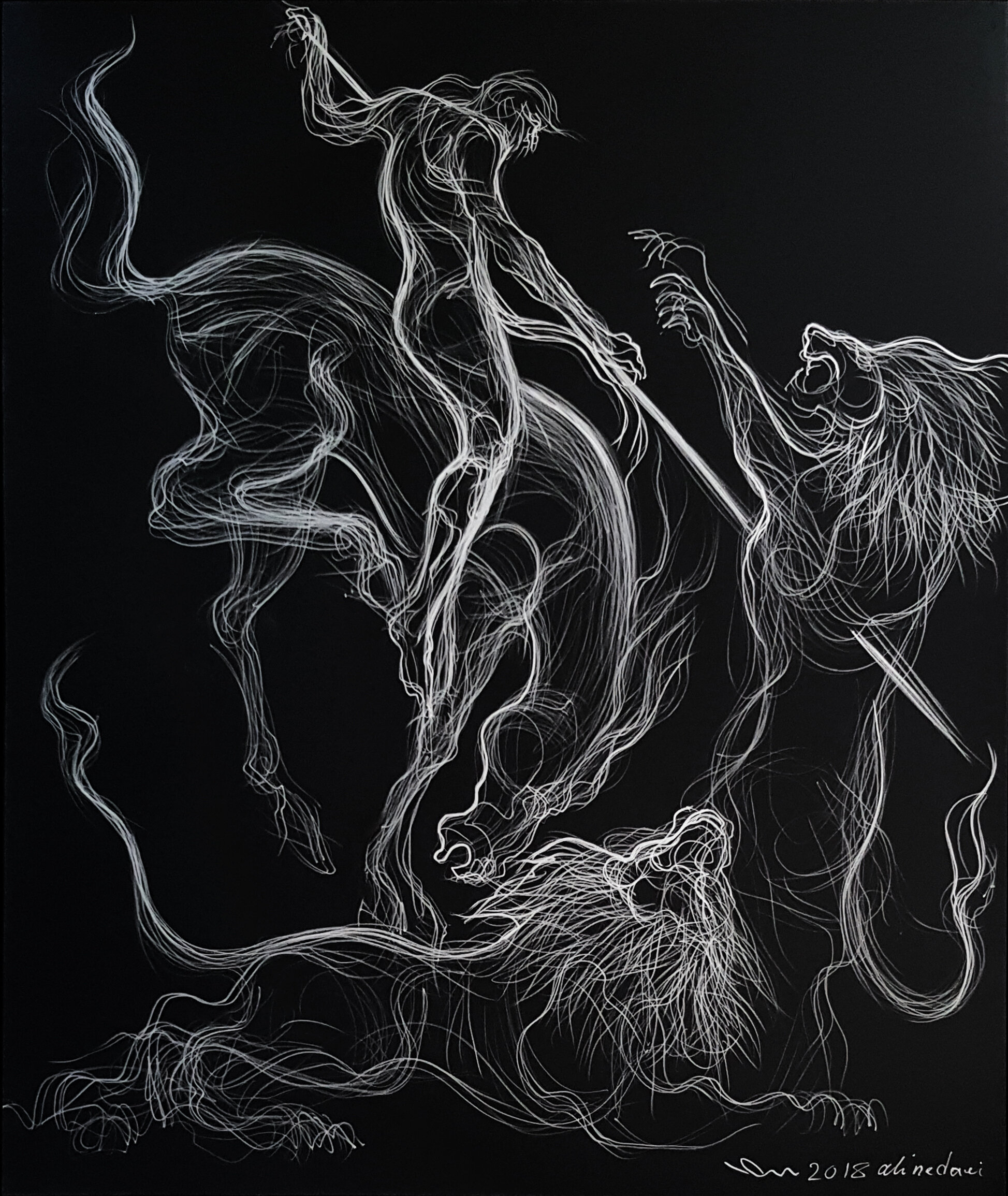

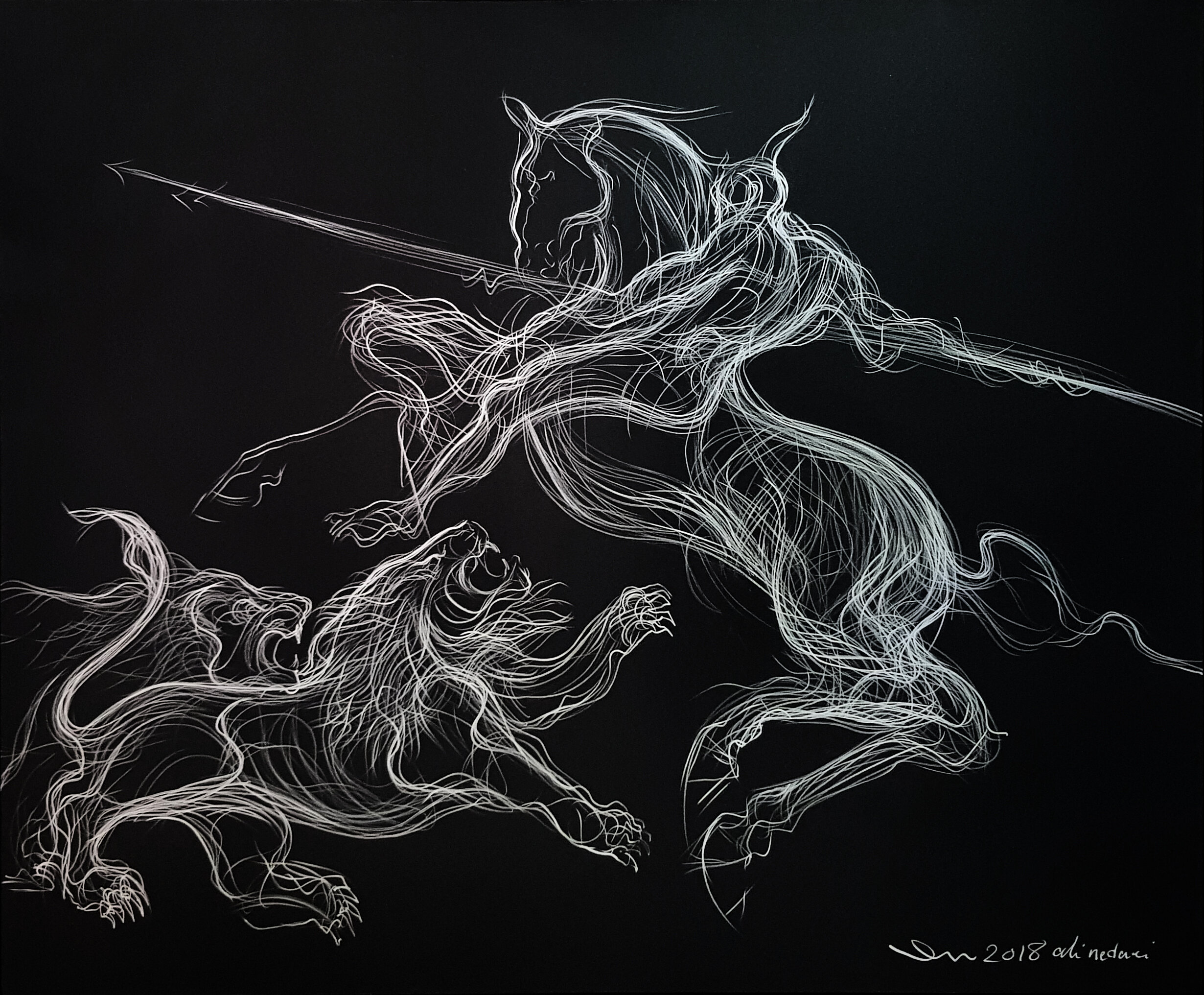

Ali Nadaei’s take on Ferdowsi sees a Bacon-esque male nude evaporating into an antique map of the Persian Empire. The anonymous body is formed out of rapid washes of paint dominated by shades of pink, red and black. It is unclear whether he is emerging out of, or disappearing into, the cartography of the land in the background. He is a ghostly apparition of national pride, either burning or burning out. Indeed, the rest of Nadaei’s work is influenced heavily by a kind of fantastical surrealism, with disappearing, hyper-kinetic bodies crafted from bright white lines, or horses bolting in from stage-right to greet hooded figures flanked by transparent snakes. His distillation of the tale of Sohrab is turned into a metaphysical tragedy rather than a triumph of morals: where Sohrab had to undertake a trial-by-fire to prove his innocence after a false accusation, in the Shahnameh tale he originally emerged unscathed. Here, however, he lies aflame, balanced precariously on a see-thru box beyond any apparent material stability. It’s a very different retelling.

What emerges from the work of these artists collectively is a deep sense of Iranian manhood being rooted in the mythical, the historic and the national. In many ways, it is a vision of a concept of ‘the man’, rather than a reflection of the individual himself. This is where the work of Ebrahim Faraji (1940 - 2004) comes in. Over the course of his understated career, Faraji produced a number of brooding portraits with an angularity and a post-impressionistic spikiness that puts them, at least stylistically, halfway between Schiele and Van Gogh. The take-away however, is entirely Persian. There is a head-and-shoulders rendering of Rostam in disguise (Untitled – 1967), identifiable only by his distinctive leopard-head hat. In another (Untitled – 1966), the subject, possibly the artist himself, sits with the elegant and serene countenance of an ancient king. His face is elongated into a noble rectangle, which is mirrored by the extension of a headpiece. He is flanked by blockish juts that resemble the audience hall of the Apadana at Persepolis, the seat of power of the Parthian and Sasanian kings of ancient Iran. He has the upright rectilinearity of a rock relief of Darius the Great. Next to his head floats the symbol of the Farvahar, one of the earliest known symbols of Iran and of the country’s early adherence to the Zoroastrian religion. What Nadaei has done is to distil all the elements of heritage that still speak so loudly to an Iranian idea of manhood, into an image that is both sharply modern and archly ancient.