Michael Rakowitz – Whitechapel Gallery Survey Show 2019

I met Michael Rakowitz at the Conduit Club, where he was giving a talk to coincide with the opening of a major retrospective in East London’s Whitechapel Gallery. Though based in Chicago, the Iraqi-American artist’s first survey show is being staged here in London, where he has enjoyed a relatively high profile since winning the Mayor’s prestigious Fourth Plinth commission in 2017. Spread over six rooms and two floors, the exhibition features eight installations spanning twenty years of creative output.

Unlike so much contemporary art, offering moralising social commentary from a safe distance, Rakowitz leverages his artistic practice to probe uncomfortable questions and incite change. His first major work, paraSITE (1998) – involved crafting custom-built inflatable homeless shelters using recycled material and attaching them to warm air vents at street level. The shelters were distributed in multiple American cities, and Rakowitz invited participation from the homeless people in creating his designs. ‘I make work at the intersection of problem solving and trouble making,’ he says lightly. These inflated, amorphous miniature homes served not only to shield their incumbents from the elements – but to draw attention from passers-by, and on occasion, the cops. In this complex process of simultaneously solving and problematising, Rakowitz isn’t afraid to get his hands dirty.

White Man Got No Dreaming, 2008

Rakowitz first visited London as a child in 1984. He recalls fondly a trip to the British museum, where his mother pointed to an ancient Assyrian frieze and identified it as ‘the first ever cartoon strip.’ Young Rakowitz’s imagination was captivated, and to this day he revels in teasing out such parallels between past and the present. The prominence of history in his work is evident from the start of the Whitechapel show, which opens with White Man Got No Dreaming, a work created for the Sydney Biennale in 2008. It is an imposing wooden construction based on Vladmir Tatlin's utopian Monument to the Third International, designed in 1919 but famously never realised. Crowned with an aboriginal flag, the tower is a political statement, calling for affordable community housing in Sydney. By appropriating a piece of Soviet architecture, in turn inspired by Bruegel, Rakowitz plays with multiple layers of cultural association in a pointedly politicised artwork. As Rakowitz’s fascination with social and cultural history emerges throughout the show, these art historical references seem strikingly fitting. ‘It was never just the art history’, he stresses, describing his early fascination with the subject. ‘It was about what the art was trying to say.’

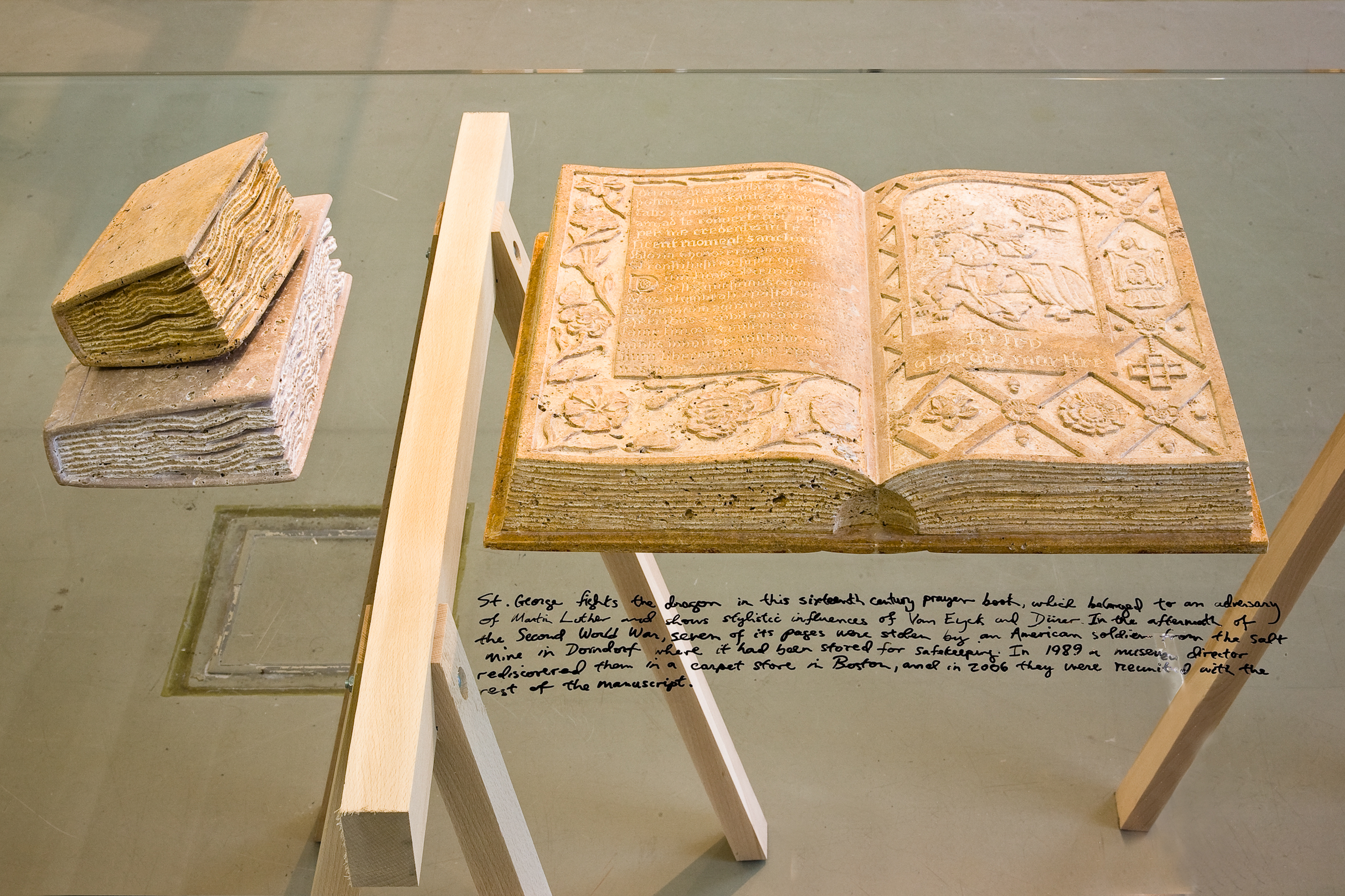

Room two is dominated by What Dust Will Rise (2012). The project is a dialogue between two historic moments of destruction: a Nazi conflagration of Jewish literature in the German town of Kassel in 1939, and the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamyan Buddhas in Afghanistan in 2001. Using old photographs of the burned books, Rakowitz ran carving workshops for Afghan locals, who then produced recreations out of stone, immortalising the lost books and transforming ‘cultural trauma into monuments to knowledge’. They are displaced beneath glass cabinets, their captions writ directly onto the glass in the artist’s distinctive loopy handwriting. Not only does this force visitors to get right up close; it allows for the kind of intimate union between artist and audience traditionally precluded by impersonal gallery labels. The surrounding walls are lined with cabinets of curiosities, seemingly populated with geological specimens, each precisely labelled. Drawn closer by Rakowitz’s academic inscriptions, we are confronted with dust collected from the site of destroyed Buddhas, and exploded artillery shells found among the ruins. Scribbled alongside are the chilling words of the Taliban perpetrators: ‘we are only breaking stones.’ There is a also piece of coloured granite from the floor of the World Trade Centre; a shard of German shrapnel from the First World War. The common denominator needs little explanation.

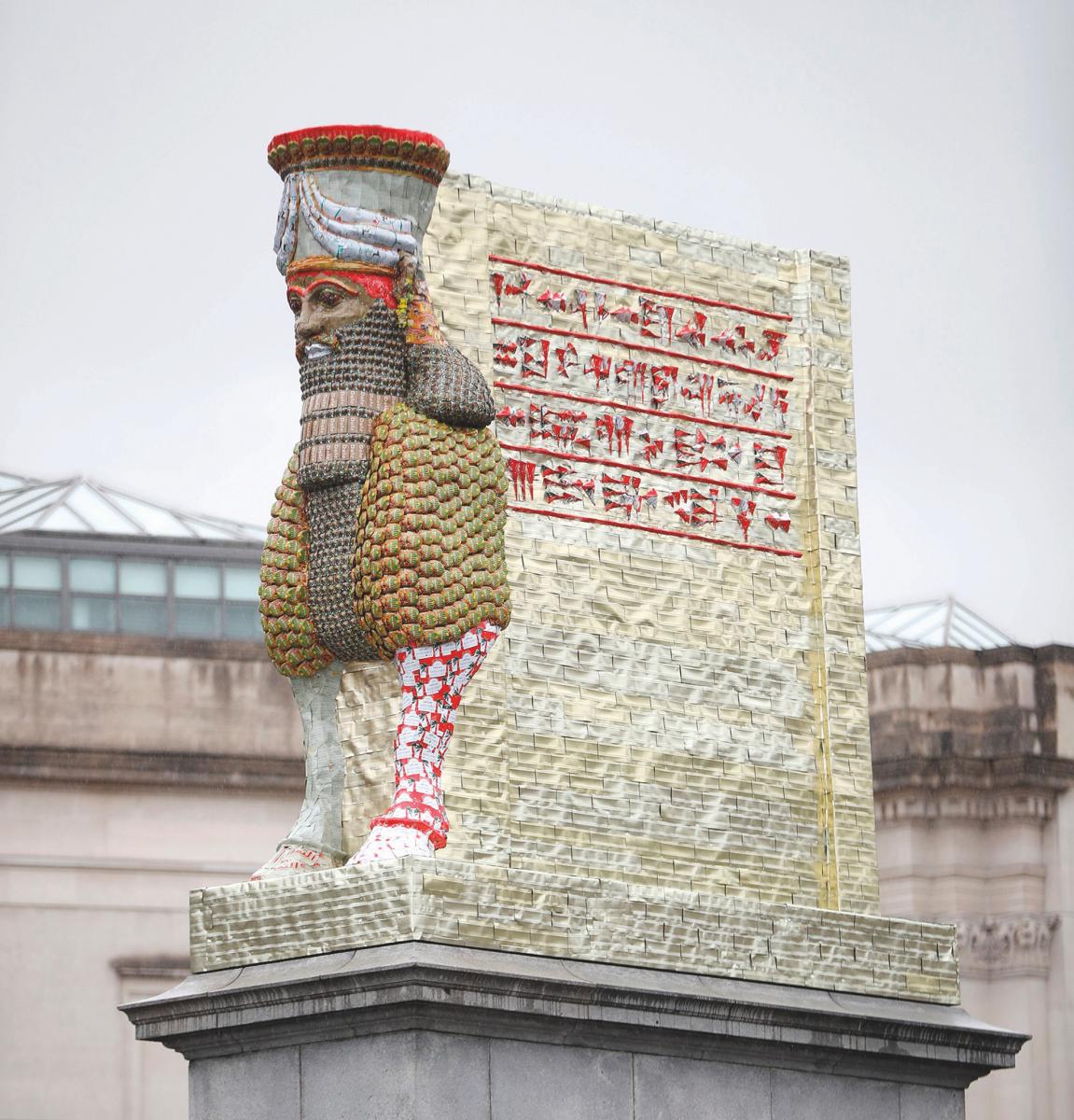

The theme of creation from destruction recurs upstairs, with The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, an ongoing project Rakowitz began in 2007. Artefacts looted from the National museum of Bagdad following the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 are reconstructed to the exact scale of the originals but crafted from recycled Iraqi food packaging. They are not intended to replace the lost objects, but to commemorate their absence. The difference is subtle but significant. Rakowitz describes them as ‘ghosts’, because ghosts always return looking different. They haunt, yes, but can also comfort. ‘I’m attracted to work that can make you feel really good and really bad at the same time,’ he explains. If good is ever to prevail, art mustn’t shy away from all that is evil. Why, then, does he spotlight the destruction of objects rather than the loss of lives? Rakowitz pauses a moment, before stating matter-of-factly that he was brought up by Jewish parents to believe that ‘when books burn, people do too’. He offers that destroyed artefacts stand for the destruction of civilisation itself. The installation culminates in a vibrant reimagining (again, using packing) of sculptural reliefs from the ancient Palace of Nimrud, destroyed by ISIS in 2015. They are discreetly accompanied by a quote from Sheik Khalid al-Jabbouri, a local commander. “I wasn’t as devastated when they destroyed my house or when they killed some of my relatives because this is life – all of us die. But Nimrud was like a part of our family. This heritage was part of our lives, part of all of Iraq’.

The maquette for Rakowitz’s winning proposal for the Mayor of London’s fourth plinth programme, currently standing proudly in Trafalgar square, is arguably the climax of the exhibition. The Lamassu was a large winged bull with the head of a man, which guarded the entrance to the Nergal Gate in Iraq from 700 BC until its destruction by ISIS in 2015. Examined at close range, this small-scale version reveals the intricacy and sheer beauty of the beast, crafted using 10,500 vibrantly coloured date syrup cans. Rakowitz reopened his grandfather’s import company to obtain the syrup cans: once a cornerstone of Iraq’s economy, the date trade has been devastated by war in recent decades. Due to their lustre, sculpture appears to glisten in London’s occasional sunshine. By sheer coincidence, the scale of the Lamassu perfectly matched that of the vacant plinth, though Rakowitz expands on the many ways the work is site-specific. The Lamassu has its back turned to the National Gallery and its canonical Western masterpieces, and confronts Nelson atop his phallic column, challenging its celebration of war. It bears witness to the increasingly frequent rallies and protests passing through the square. It is a vivid reminder of London’s terror threat, particularly the horrors inflicted by ISIS just two miles away in 2017, within months of Rakowitz winning the commission. The Lamassu is a masterwork, not only because of its striking visual beauty, but because of its universal resonance: belonging to Iraq, to Londoners; to the 20 million people who will see it over the course of occupancy. It is deeply moving. As critic Adrian Searle wrote simply upon seeing it for the first time: ‘my heart is in my mouth’.

The Whitechapel show encompasses a dizzying range of subject matter: from date syrup to the Beatles; Missouri housing estates to terrorism. I had feared this breadth would result in an overwhelmingly eclectic survey show; a series of distinct projects gathered under one roof – but I was wrong. The exhibition felt truly cohesive, unified by themes of serendipity, destruction and hope, and a tone that is both playful and political. Whitechapel’s lofty galleries echo with Rakowitz’s zealous imagination and frank wit. His ongoing projects feel like living organisms, with you, the viewer, a vital participant in their creation. Not only do his themes traverse time and place, they are timely: social injustice, belonging and exile, terrorism, the fragility of heritage. What’s more, Rakowitz was exploring these themes through his art long before far-right politics, the migrant crises, and ISIS brought them to the forefront of our collective consciousness.

Rakowitz success shows no sign of slowing, and he looks set to become one of the most important American artists of his generation. All the more reason, then, to visit the Whitechapel show and take a closer look at the Lamassu before it departs Trafalgar Square next year. Which brings us to one final question for the artist. Where will the winged bull go, when its time on the Fourth Plinth is up? ‘It will go back to Iraq’, he smiles. ‘It will fly back home’.